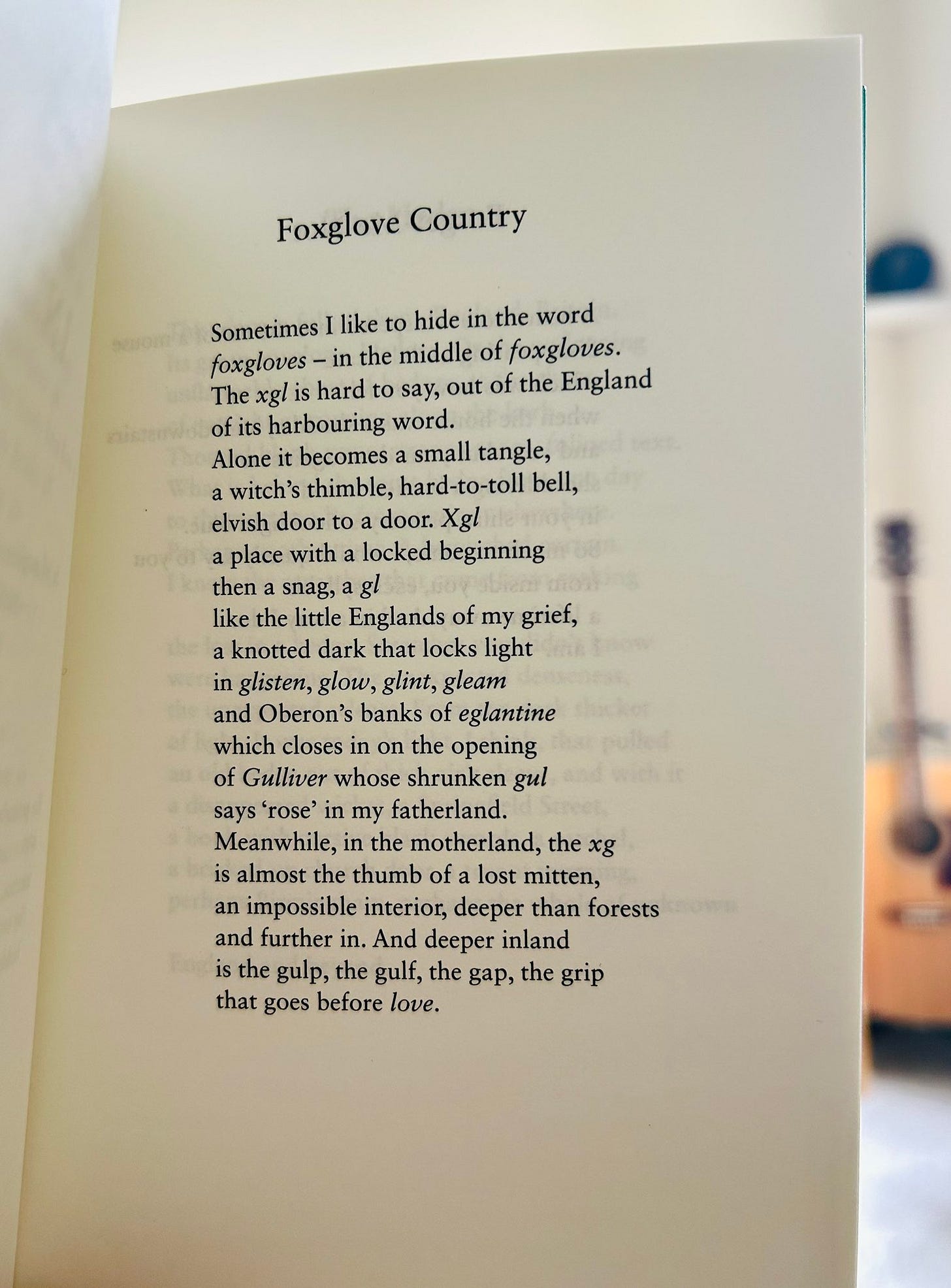

#4: Zaffar Kunial's 'Foxglove Country'

an impossible interior, deeper than forests / and further in.

When we seek to understand a place, we might start by identifying the details that comprise it: topography, climate, flora and fauna, population demographic, cultural milieux. What happens when we apply this same lens to unpacking a single word? For those of us whose relationship to our own identities is uncontested, legible, accepted, language functions as an opening by which to reiterate our cultural positionality. For others—as Zaffar Kunial’s prodigious ‘Foxgloves’ explores—language (and place) is a lock that necessitates picking; it is a site of exclusion and indignity, or perhaps, through the poet’s careful and dignified unwinding, a site of enquiry and personal sense-making.

As this poem demonstrates, there is so much that may be uncovered by examining the mechanics of language—especially when it is unwieldy, or bewildering, or demanding of explanation. English, in particular, is a deeply weird language, containing the discombobulated fuselage of its many and varied influences. And Britain is a weird country. It’s a nation highly selective about who is welcome, who belongs—and who is not and doesn’t. The way this is articulated or manifested is frequently subtle: embedded in the minutiae of language and accent and behaviour and vague auspices of ‘tradition’.

Kunial approaches the foxglove—this stalwart of the traditional English garden—as a botanist of the word itself, cataloguing the indiscretions, allowances, allusions, composite parts held inside it. The poem’s speaker is right, the centre of the word does indeed catch in the throat: a small hard syntactical core that snags closed, refuses access. Yet there are other surprises: a lock of shimmering glint, glimmer, in the ‘gl.’ So, too, there are resonances of the self as multivalent—diasporic but quietly coherent. The very same glottal tone contains the opening of Gulliver, that famous figure of the Anglophone literary canon, and is echoed by the speaker in the word for ‘rose” in my fatherland.’

And so where ‘Foxglove Country’ (and the T.S. Eliot Prize-shortlisted collection, England’s Green, from whence it comes) lives isn’t within the cosy enclave of simple and unequivocal acceptance. No, instead, the poem takes up the scalpel of language to dissect Britain’s self-mythology, to complicate the pastoral—magnifying the ways that cultural tradition can become a pastiche of itself and, in so doing, circumscribes who is permitted to engage with it. Kunial writes into a space of fluid liminality: that of variously understanding oneself to be embedded in and alien to a place, of language as both spacious and imperfect, of what it feels like—really feels like in a physical, acoustic way—to exist within the gaping maw of such contradictions. And not just to exist—but, from within these ambiguous realities, to build and negotiate a home.

Until next time,

Maddy

PS: Here’s Kunial reading ‘Foxglove Country’ aloud, and I recommend listening; this is a poem that wants to be heard aloud:

Thank you for reading Field Guide!

One small housekeeping note before we go: you’ll note that I am also offering a paid subscription option. It’s not obligatory and you’ll receive all the same content regardless. Paid subscription will simply function as a “tip jar” to help compensate me for the time and labour that goes into researching and writing this newsletter. If you’re feeling generous and are able to do so, you can support Field Guide by upgrading to a paid subscription below. Either way, I’m grateful that you’re here.